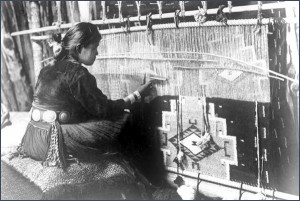

Art-making, like learning and languaging, has its foundation in the psycho-biological meanings inherent in physical movement.

Beginning in utero, experiences of movement-sound—our first perception—lay the foundation for non-verbal knowing, meaning-making and relationship.

Early childhood experiences of moving and sounding in the forces and dimensions of our concrete world build internal prototypes that match reality. These prototypes—such as basic geometric shapes, color hues, textures, tastes, volume, weight, direction, balance, rhythm, sound, tone, timing, and so on—are the building blocks of art-making. They are developmentally expressed in children’s art-making worldwide1.

I agree with Paleolithic scholar and artist R. Dale Guthrie, that original human art-making was an improvisational play of experience and discovery. He writes that art “was a kind of play that was specifically targeted and specifically dedicated to exploring and sharing new perceptions…Paleolithic art is that first clear spoor of advancing creativity in the human line”2. That is, art-making was originally about art for life sake.

I agree with Paleolithic scholar and artist R. Dale Guthrie, that original human art-making was an improvisational play of experience and discovery. He writes that art “was a kind of play that was specifically targeted and specifically dedicated to exploring and sharing new perceptions…Paleolithic art is that first clear spoor of advancing creativity in the human line”2. That is, art-making was originally about art for life sake.

Engagement in art-making makes evident the inherent aesthetic nature of the way in which we humans organize, reveal, make meaningful, and celebrate—make special3—our reality. Through aesthetic intelligence we intrinsically make sense of our biological, social, cultural, and spiritual lives.

1For ‘developmentally expressed in children’s art-making worldwide’ see:

Rhoda Kellogg: The Psychology of Children’s Art.

Sylvia Fein: First Drawings: The Genesis of Visual Thinking.

2R. Dale Guthrie is author of The Nature of Paleolithic Art

3“Making Special” is a phrase by Ellen Dissanayake, scholar in the anthropological study of art and culture.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Photo credits: Barbara Cole Kirk, Friend, Rebecca R Burrill,

Fleet Moves, Google Search, Friend, Barbara Cole Kirk, Respectively

Watercolor: Rebecca R. Burrill (2004)